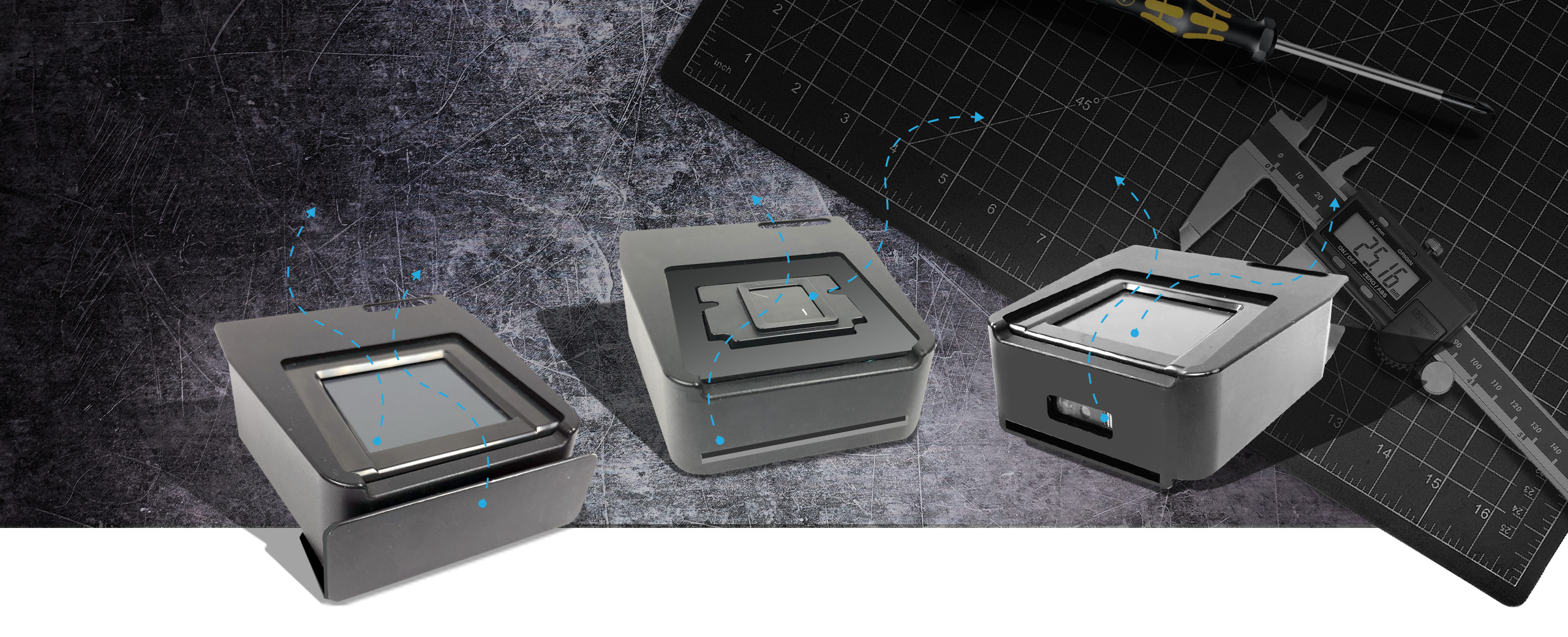

Los Angeles, CA (April 4, 2018) – AMREL, the premier provider of mobile biometric solutions and rugged computers, introduces the BioFlex® S (Gen 2), a single-finger biometric smartphone solution for security and law enforcement professionals. AMREL’s rugged BioFlex S module and Suprema ID’s BioMini Slim 2 scanner work together to convert Samsung Galaxy S7 (S8 coming soon) smartphones into biometric devices for mobile identification.

Militarization of Police –Rugged Radio Podcast

As the violent images of Ferguson, Missouri permeate the media, a debate has erupted about the “militarization of police.” Is it time to reconsider the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) 1033 program, which gives surplus military equipment to police departments? Listen to podcast by clicking the bar at the top of the page.

Rugged Radio explores the world of rugged computers, unmanned systems, and related topics. The opinions discussed in this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of AMREL, its employees, clients or partners.

Last July, Dallas police killed a suspected gunman with an Unmanned Ground Vehicle (UGV). By any conceivable stretch of the imagination, this was a “good kill.” The gunman had murdered 5 policemen, threatened to kill more with hidden bombs, and refused to give up even after hours of negotiations. A credible threat against civilians had been made. The threat had to be neutralized in a timely fashion. Using an UGV reduced the danger to officers, and protected civilians at the same time.

We are not sure what kind of robot was used, but it was probably one designed to detect Improvised Explosive Devices (IED). Ironically, the robot, which was most likely designed to counter explosive devices, killed the gunman by detonating a bomb (a pound of C4 explosives).

Sources claim that the UGV was a Remotec Andros F-5 model (some say it was a MARCbot, but this appears to be speculation). We do know that the UGV was remotely controlled. Both the MARCbot and the Andros F-5 have been used in overseas combat operations.

The tactic of jury rigging an explosive device to a UGV in order to perform a kinetic action is not a new one. The Brookings Institution reported in the “Military Robots and the Laws of War” that soldiers would strap Claymore anti-personnel mines to UGVs in attempts to kill insurgents.

Some are alarmed that police used military equipment and tactics on American soil. Many feel that the whole “killer robot” scenario was just plain ominous. The following quotes are typical.

“The ‘targeted killing’ of a suspect on ‘U.S. soil,’ as opposed to extraterritorial declared or undeclared war zones, where this operation also has clear precedents too, has captivated the attention of scholars and the public. … the event raises many issues about the rules of engagement and the constitutional rights of a suspect—issues that obviously the Dallas police completely skirted, and do not seem too willing to discuss in the aftermath.” Javier Arbona, Assistant Professor, University of California at Davis in American Studies and Design, UC Davis

“As with other game-changing technologies, police robotics—especially as weapons—could change the character of law enforcement in society.” Patrick Li, Director of the Ethics & Emerging Sciences Group and a philosophy professor at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, IEEE Spectrum

“…placing a bomb on a police robot with the intention to kill a suspect—if that is, in fact, what happened—would represent a major shift in policing tactics….It now appears that a tactic of war deployed on foreign soil is being used on the streets of American cities. There are still a lot of moving pieces and things to sort together in the aftermath of the police shootings in Dallas. But one thing is clear: the rules of police engagement might have just changed forever.” Daniel Rivero, Fusion

As evidenced by the above quotes, legal experts and ethicists are anxious over the use of a “killer robot.” You know who didn’t seem concerned? Police.

“Admittedly, I’ve never heard of that tactic being used before in civilian law enforcement, but it makes sense. You’ve got to look at the facts, the totality of the circumstances. You’ve got officers killed, civilians in jeopardy, and an active shooter scenarios. You know that you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do to neutralize that threat. So whether you do it with a sniper getting a shot through the window or a robot carrying an explosive device? It’s legally the same.” Dan Montgomery, former police chief, Time

I called AMREL’s Director of Public Safety Programs, William Leist, to ask his opinion. A former Assistant Chief California Highway Patrol, he has many years of police experience. He fell into the camp of no big deal.

“Deadly force is deadly force. Whether we use a bomb, a vehicle or a firearm, if the situation is such that deadly force is authorized, lawful, and necessary, the mechanism really shouldn’t matter.”

I am inclined to strongly agree with Bill Leist (and not just because he works with AMREL in supplying rugged computers and biometric devices to law enforcement). The use of a UGV in this particular instance isn’t really a game changer, as some experts are maintaining.

However, let’s be devil’s advocate and point to potential problems. There is an old saying, “good cases make bad laws” In other words, a specific high-profile instance may not be the best guide for similar circumstances in the future. Just because the use of a UGV in Dallas was a lethal operation that even Gandhi would have approved doesn’t mean that there isn’t potential for abuse.

The adoption of new technologies does not always lead to expected results. Police have expanded an application of another new technology, UGVs, beyond the original purpose. Granted, this new application is justifiable in this instance, but are we in a position to predict future consequences?

Police are being overwhelmed with technology. Law enforcement officer are dealing with a multitude of biometric devices, communication technologies, non-lethal weapons, biometric equipment, and a wide variety of computer platforms. In many departments, training has not kept up with the needs. Should there be certain minimal standards for operators of UGVs? Who sets them?

Suppose something goes wrong and a civilian gets hurt. The police will say that it’s not their fault, because the UGV malfunctioned. The manufacturer will say their UGVs are not designed for lethal operations, so it isn’t their responsibility. Granted, almost all police actions have liability issues. However, unmanned technologies pose liability problems that are beyond traditional concerns, and are major factors in slowing their adoption.

What about visibility? Whether a shooting is justified or not may depend on what a policeman sees or what he thinks he sees. Remote-controlled unmanned systems, who operators may have limited visibility, may present new problems.

Using lethal force with an UGV does not herald a new era of law enforcement. The adoption of this new technology is unlikely to fundamentally alter the current legal dynamics surrounding the use of police force. However, they may present new complications and challenges.

On May 6, 2004, the FBI arrested Oregon lawyer Brandon Mayfield. A partial print found on a bag of detonators had conclusively linked him to the March 2004 Spanish terrorist bombings. Four separate fingerprint examiners positively identified the latent print as belonging to him.

All four examiners were wrong. In fact, three weeks before Mayfield was arrested Spanish officials had informed the FBI that they had matched the partial print to an Algerian man named Daoud Ouhnane. Still, the FBI believed their own experts and arrested Mayfield. Eventually, Mayfied sued for wrongful arrest and imprisonment, as well as civil rights violations, and won $2 million.

Clearly this was a freak occurrence that couldn’t possibly ever have happened again. Except it did. In connection with a 1994 murder, examiners had positively matched Beniah Dandridge’s fingerprints to ones found at the crime scene. In 2015 new examinations disputed the identification, and Dandridge was cleared of charges. He was released in 2015 after serving 20 years of a life sentence.

Although there is no empirical scientific proof of a fingerprint’s uniqueness to a given individual, no one really doubts this is true. The real problem is latent prints, i.e. those prints found on a crime scene, which are often smudged and partial.

The very first person who doubted the usefulness of latent fingerprints was the very first person in modern times who proposed using fingerprints to solve crimes, i.e. Henry Faulds, a Scottish doctor. He wrote:

“The least smudginess in the printing of them might easily veil important divergences … with appalling results…. (police were) “apt to misunderstand or overstrain, in their natural eagerness to secure convictions.”

Despite a century plus of use by the courts, Henry Faulds objections remain surprisingly sound. No empirical or established standards exist for matching latent prints.

Nor are challenges to the legality and scientific basis of fingerprints limited to desperate defense attorneys. In 2007, a judge in Maryland judge ruled fingerprint evidence in a death penalty case was inadmissible, because it was “a subjective, untested, unverifiable identification procedure that purports to be infallible.” In 2002, Judge Louis Pollack ruled that fingerprint identification was not a legitimate form of scientific evidence. He later reversed himself. Since 1999, nearly 40 judges have considered whether fingerprint evidence meets federal or state standards for the admissibility. All have ruled in favor of the status quo, but many think that the very existence of so many challenges is worrisome. Even the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has raised doubts and has called for vigorous scientific investigations.

In fact the NAS has conducted one study about the accuracy of latent fingerprint matching. Excerpts from their conclusions:

“False positive errors (erroneous individualizations) were made at the rate of 0.1% and never by two examiners on the same comparison.

“The majority of examiners (85%) committed at least one false negative error, with individual examiner error rates varying substantially,

“This lack of consensus for comparison decisions has a potential impact on verification: Two examiners will sometimes reach different conclusions on a comparison.”

A 0.1% false positive error (claiming a match that does not exist) may not sound like much. However, consider thousands of fingerprints are processed every year. If the above false positive rate is correct, it is safe to assume that at least some individuals will be erroneously matched.

It is extremely unlikely that the courts will discard over one hundred years of legal precedent and throw out fingerprinting altogether. However, we can expect more challenges in the future and a growing skepticism among both professionals and the public.

What should Law Enforcement Officers do?

- Strictly enforce current standards regarding evidence collection and processing. This is just good police work, and will become more critical as legal and scientific challenges persist.

- Currently only about half of fingerprint examiners have passed a proficiency exam by the International Association of Identification, the profession’s certifying organization. While there is no evidence that certified examiners are less prone to mistakes, it would be appropriate if all working examiners have passed the test, if nothing else, just to deflect attacks by attorneys.

- Educate the public in general and jurors specifically. There has been growing apprehension about the “CIS effect,” i.e. the public having unrealistic expectations about forensic evidence. This had led to prosecutors explaining to jurors how the reality of forensics differs from fictionalize versions. With mounting criticism about fingerprints, prosecutors will again find themselves in the role of educators.

- Change the standards of expert testimony. Currently, examiners are trained to testify only when they “’absolutely certain.” This is a highly unscientific standard, and examiners should be taught to state their opinions in the terms of probability. Of course, research has to be done to establish such probabilities; none exist now. There is no scientific research about the chances of two individuals exhibiting the same or similar ridge characteristics.

Although controversy has been so far limited to latent prints, it is reasonable to extrapolate from current trends challenges to verifications and enrollments as well. Police officers are already powerfully motivated to take good quality prints from enrollees. Access to the FBI’s Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) require print images that meet high quality (all AMREL handheld biometric devices meet FAP-45, an extremely stringent standard). Good quality sensors, especially Light Emitting Sensors (LES), require fewer retakes, and save time. In addition to these established reasons, high-quality fingerprint images also provide a credible defense against legal attacks.

In the long run, it is up to the court of science, not the court of law, to establish the true credibility of fingerprint evidence. In the meantime, law officers’ only option is to pursue their duties with excellence and the best equipment they can acquire.

The one city in the San Francisco Bay area that I would expect to have bad police-community relations would be Richmond, California. I never ever felt safe there.

I don’t scare easily. In the early 90s, when I worked in an Oakland office, my secretaries reported to me that they heard automatic gun fire every night. Yet, when I walked around Oakland (often stepping over hypodermic needles), I never felt threatened.

On the other hand, Richmond, which is located across the bay from Marin County and north of Berkeley, had a dangerous vibe in those years. None of my friends would go there (not even the guy who once lived in the slums of India).

Once I stopped at a train station in Richmond and saw a crowd of about a dozen or so middle-school children running. I asked them what was going on. A boy laughed and said, “We stole a gun from a cop.” He looked about 10-years old.

This is why I was greatly surprised to learn that Richmond has had not only a dramatic drop in homicides, but an astoundingly low rate of police officer caused shootings. Common sense measures almost eliminated civilian deaths at the hands of law officers.

I asked Albaro Ibarra, AMREL’s Senior Marketing Manager, and former police officer what he thought of the article that described the low level of police-involved shootings. He replied,

“Great piece. In my Academy days they taught us to respond with the level of force that was needed. The dangerous thing was that each officer had their own opinion about the level of threat they were in. There were some officers that were more likely to pull out their weapon because they felt there was a threat. Maybe it was because of the officer’s personal strength or their lack of confidence in being able to scale down a situation.

“A good example of this was when we confronted a very upset lady who was wielding a knife. The situation around us was tense and some officers pulled their guns. One of our lead officers was an ex-NBA player and self-defense trainer. He never pulled out his gun. His confidence in his abilities resulted in him disarming her without firing a shot.

“I believe we didn’t get enough or any training on how to scale down a situation. That would have been very helpful to develop greater confidence within the officers to know that they could handle a situation without pulling their side arms.

“The article touches on how there’s a level of trust between Chief Chris Magnus and the Richmond community. I saw this with veteran officers who often worked the day shift. They enjoyed engaging with the community, and built personal relationships. They would often like to do their work on foot, not in vehicles.

“Some of the new officers, who often worked the night shift, were driven by violence and adventure. They had less community involvement and escalated situations more frequently.

“During those times we lacked the computer technology that AMREL (rugged mobile computing and biometric solutions) today offers to the Public Safety sector. The ability to be more mobile and be amongst the community helped reduce the feeling of US against THEM and develop more a feeling of ALL OF US. Utilizing the modern technologies that are now offered would have made my work more efficient, and engage more with community. It would have increased the feeling that the Police Department is there to Serve and Protect and not just to Enforce.”

The following article was originally published in Vox

You don’t expect to see a police chief at a protest against police brutality. But when Richmond, California held a protest against recent police shootings of unarmed black men, Richmond’s police chief, Chris Magnus, was there on the front lines, holding a #BlackLivesMatter sign.

Magnus was criticized by his local police association for his appearance at the protest — the association claimed that they didn’t have any problem with the message, but it was against California law for him to appear in “political activities of any kind” while in uniform. But Magnus is clearly doing something right in Richmond, a Bay Area town of 107,000. When Vox talked to Magnus earlier this year, the cops hadn’t killed a civilian in five years. (A Richmond police officer fatally shot a civilian on September 14th, 2014.)

Magnus cautions that “policing is local,” and that what works for his department might not be appropriate for others. But here are some lessons he’s learned about leading a department that doesn’t use force as a first resort.

1) Don’t recruit cops by promising violence and adventure

“You have to be thinking, as a police administrator, about what kind of folks you want to attract to your department, and how you do that. You look at some departments’ recruiting materials, and you see guys jumping out of trucks in SWAT gear and people armed with every imaginable weapon. There are clearly situations where that is a necessary and appropriate part of police work. But having said that, that is by far and away not the norm.

“My goal is to look for people who want to work in my community, not because it’s a place where they think they’re going to be dealing with a lot of violence and hot chases and armed individuals and excitement and an episode of Cops or something. I want them tactically capable to handle situations like that, but I want them to be here because they’re interested in building a partnership with the community. They’re not afraid to have a relationship with the residents that they serve, in terms of getting out of the car and talking to people. Those are messages that have to be sent early on, before people even get hired.”

2) Train officers not just in what they can do, but in how to make good decisions

“It’s important that officers have training that involves more than just being proficient in the use of a firearm. Obviously that’s something they need to be able to do, but a big part of our training around use of force, specifically with use of firearms, is training in decision-making under stress. How and when do you consider the use of deadly force? What are the other options that were available to you?

“There are still a lot of police academies in this country, whether they’re through police agencies, colleges, or other institutions, that are probably not as far along as they should be in some of these areas. As a field, we can do better.”

3) Give cops extra training in interacting with mentally-ill people — and teenagers

“We’ve done quite a bit of training, with our school resource officers and our juvenile detectives, about some of the better ways to communicate with youth — what approaches might be most appropriate if you have to use force. Some of that’s really about brain development, and we’re learning that young people really do respond differently than adults do.”

“We do a lot of training dealing with the mentally ill. We have officers on all of our shifts who have gotten even more detailed and involved training — crisis intervention training — dealing specifically with mentally-ill individuals. That covers understanding what the signs are that someone may be in a mental-health crisis, understanding about medications and the impact of those medicines that a lot of folks might be on, understanding what happens when they’re not taking their medication, and getting better knowledge on how to interact or engage with people who are in crisis.”

4) Training doesn’t stop when you get out on the street

“Our officers go through what is anywhere between six and eight months of additional training once they hit the streets. That involves being teamed up with other officers who are trained as trainers, and who provide them with ongoing and regular evaluation about what they’re doing and help them learn from their mistakes in a more controlled setting.”

5) Remember that you can kill someone with a Taser

“Part of the problem with Tasers out in the community is, perhaps, this particular piece of law enforcement equipment has been misrepresented to suggest that it always can guarantee a good, less-than-lethal outcome. And that’s not true. People have complicated health histories which you can’t possibly know, most of the time, when you’re dealing with them. There may be a lot of circumstances that complicate the use of a Taser that you couldn’t know in advance.

“The vast majority of our Taser use involves displaying it and informing the suspect that resisting arrest will result in them being tased. In other words, we don’t even necessarily deploy it. And that’s enough, most of the time.”

6) Be proactive in addressing officers who use a lot of force — before they become a problem

“We have a database in which we track each officer’s history in terms of how they use force. If we see an officer who seems to be using force more than somebody else, we take a more careful look at that. That doesn’t always mean that the officer is doing something wrong or that they’re just predisposed to use force. It might have to do with the area that they’re working, the incidents they’ve been dealing with. But it still never hurts that we look more carefully and try to be as proactive as possible in addressing a situation before it becomes, potentially, a problem.”

7) Don’t be afraid to fire someone who’s not cut out to be a police officer

“It’s hard when you’ve invested as much as a year or more into training somebody. But there are clearly some folks who can’t multitask, they can’t make good decisions under stress, they’re not effective communicators. For whatever reasons, they’re not cut out to be police officers. Part of the challenge of a professional police department is to make sure those folks are separated from service early on. So you have to be willing to do that — and to have the local political support within your city to do that.”

8) When force really is needed, a little community trust goes a long way

“The use of force is something that, when people see it, they’re horrified by it. Even though it may be completely legitimate and appropriate in a larger scheme, it’s not easy to watch, and it’s even more difficult to have to be part of.

“You have to have an underlying relationship with the community so that there’s a level of trust and understanding and people are willing to hear you out about why force was used in a set of circumstances. And the community can trust that when mistakes are made — which sometimes happens — your department’s going to learn from them so they’re not repeated.”

9) Police departments can’t do sufficient training without resources

“It’s totally appropriate and important that we have this national conversation about use of force. But I hope along with that is a commitment to the idea that it takes resources and financial support to do this kind of training. A lot of departments don’t even have the personnel that they need to handle many of these situations. They certainly don’t have the resources to commit to that type of training and equipment. So then you have cops that are really left with a knowledge gap and a resource gap. And I’ve worked in some smaller departments, where I’ve seen that it’s very tough.”

The headlines are clear. Murder Rates Rising Sharply in Many U.S. Cities declares the New York Times. Echoing other media outlets, it ominously describes sharply increased homicide rates in at least 30 American cities. New York, Philadelphia, and Dallas all report a rise in murders. After decades of a decreasing crime rate, why is there a sudden uptick?

The murder rate is still low – for us

To get an idea of why the murder rate has suddenly increased, it would be good to know why it went down in the first place. For example, in 1990, New York City had more than 2000 homicides. By 2014 that number was just over 300. Even with the recent increase, the national homicide rate is just a fraction of what it once was (America still has one of the highest rate of violent crimes in the industrialized world. We’re number 1!).

The only honest answer about the cause of the decrease in the murder rate is that we don’t know. Some point to improved policing policies. Some say it was an increase in mandatory sentencing, while others cite the removal of lead from our environment and even legalized abortion as possible causes (Vox). This is a topic that has been extensively studied, but the conclusion of the academic world seems to be a collective shrug. About the only thing we know with any certainty is that the much celebrated “broken windows” policy had nothing to do with the national decrease.

A watched cop never works

The fact that we do not know why crime went down in the first place has not stopped some from speculating about the recent reported increase. FBI Director James Comey has coined the term “Ferguson Effect.” According to his theory, increased scrutiny of the police by the public and video cameras has had a chilling effect. Police are too intimidated to do their jobs.

Comey has been forthright in acknowledging the lack of evidence for his idea (Guardian). As pointed out by others, the increase in crime, at least in St. Louis, predated the troubling events in Ferguson.

Whatever the evidence actually is, there is something insulting about this theory. Is the FBI Director really arguing that if police can’t shoot and beat up unarmed civilians, they won’t fight crime? Are police really so sensitive and immature that in the face of public criticism and scrutiny they won’t carry out their critical duties? If this is true, then the anti-police brutality activists have underestimated how bad the situation is.

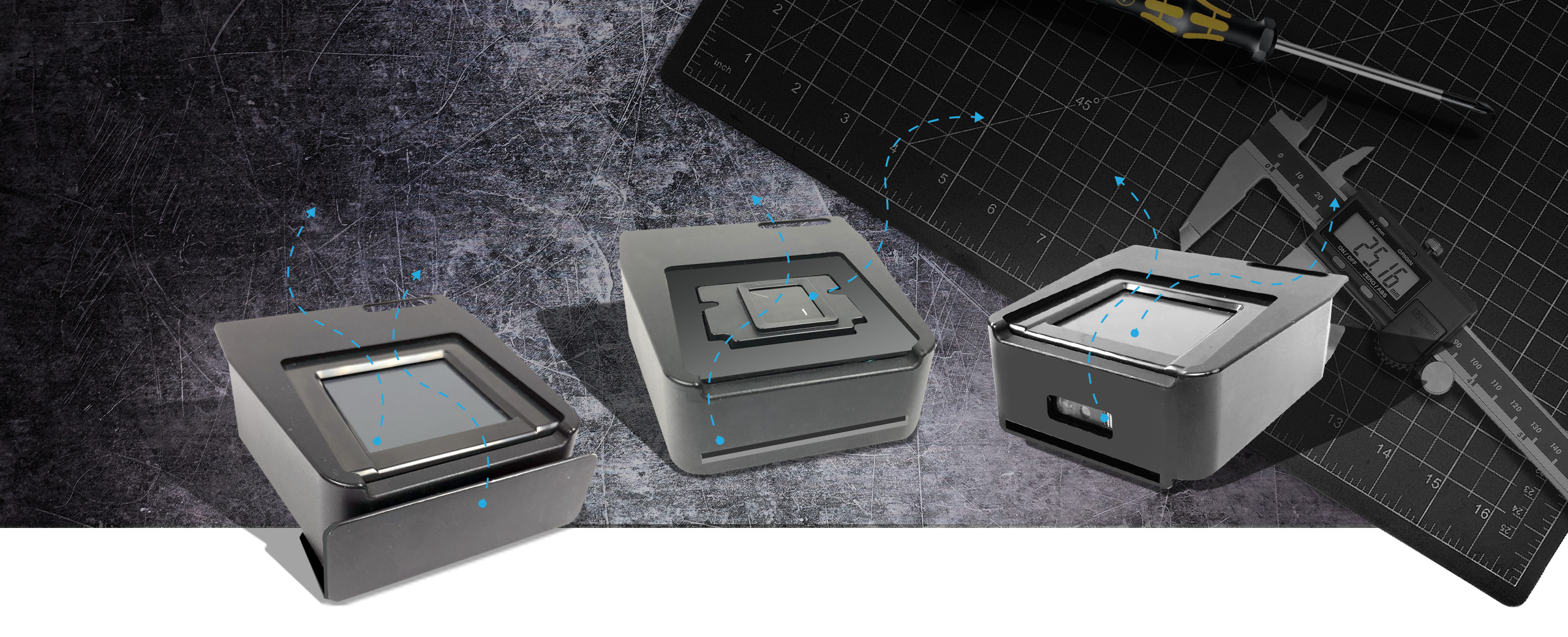

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER SMART CARD READER MAGNETIC STRIPE READER 2D BARCODE READER

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

Compatible models:

BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models:

BioFlex® Smartphones

Too darn hot

Alternative theories for the increase in the homicide rate are rare (for reasons which will be discussed below). On my own, I can think of at least two other possible causes.

One of the oldest and strongest correlations observed by social scientists is the relationship between temperatures and crime. When it gets hotter, crime goes up. The summer in 2015 was the hottest in 135 years (Huffington Post). The connection between heat and crime is so well-known that I am a bit surprised that no one in the media has mentioned this as a possible cause.

The second possible cause is even more controversial, but has important proponents. “The proliferation of firearms is one of the factors behind a rise in homicide rates in many U.S. cities this year, according to senior law enforcement officials at the International Association of Chiefs of Police conference in Chicago” (Business Insider). Furthermore, as the New York Times reports about recent new gun laws, “Nearly two-thirds of the new laws ease restrictions and expand the rights of gun owners.”

More guns, more crime, asserts this theory. For a variety of reasons, I do not believe this is even remotely correct, but it has as much evidence, if not more, as the “Ferguson effect.”

You may have heard about the “Ferguson effect,” but not of competing theories. Why? Because when researchers studied recent patterns of criminality, they discovered there has been no increase in homicide rates.

Statistics are pure evil or the science that even smart people hate

I have studied statistics as an undergraduate at Yale and at a graduate level for a healthcare course. When people ask me about it, I point to my bald head, and state that “Before I studied statistics, I had hair.” I’ve seen brilliant mathematicians and physicists despair when confronted with the challenge of analyzing probabilities.

So it is with a great deal of trepidation that I embark on a discussion of the statistics behind the crime wave. Don’t worry; I will try to keep this as simple as possible.

It is very easy to misunderstand or misrepresent statistics. For example, the New York Times article cited at the beginning of the post describes an increase of homicide in 30 cities. It doesn’t mention the decrease in homicides in dozens of other cities, such as Indianapolis, San Diego, and Columbus. As hard as it is to believe, simple cherry picking of evidence is a major factor contributing to the media’s outcry about the so-called crime wave.

To be fair, there has been an increase in the murder rate, at least for some of the largest cities, but it is far from significant. Take a look at the following statistics:

Source: Washington Post

Source: Washington Post

Looks pretty bleak, right? Homicides have definitely increased. Now add a little more information:

Even with the so-called “sharp increase,” the homicide rate is still lower than it was in 2012, or any other time since 1985. With the added information, the increase in the homicide rate doesn’t look as dire as it did before.

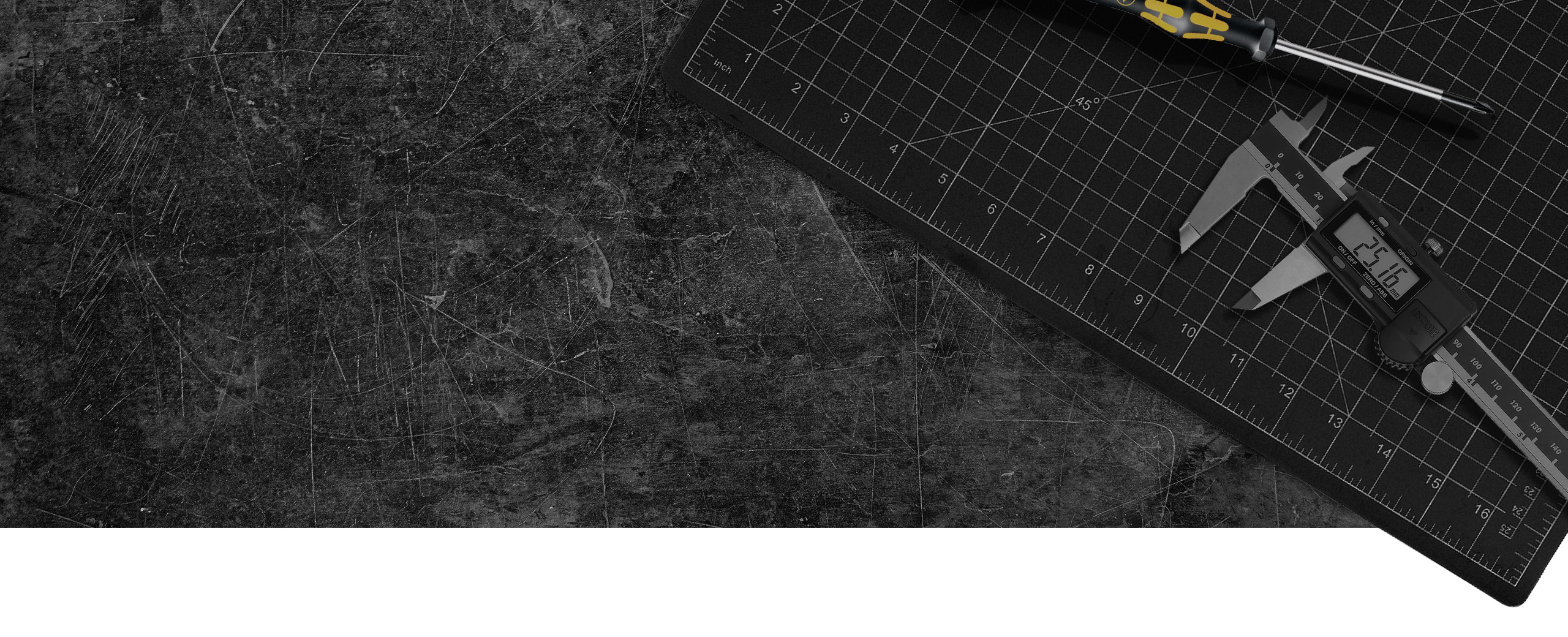

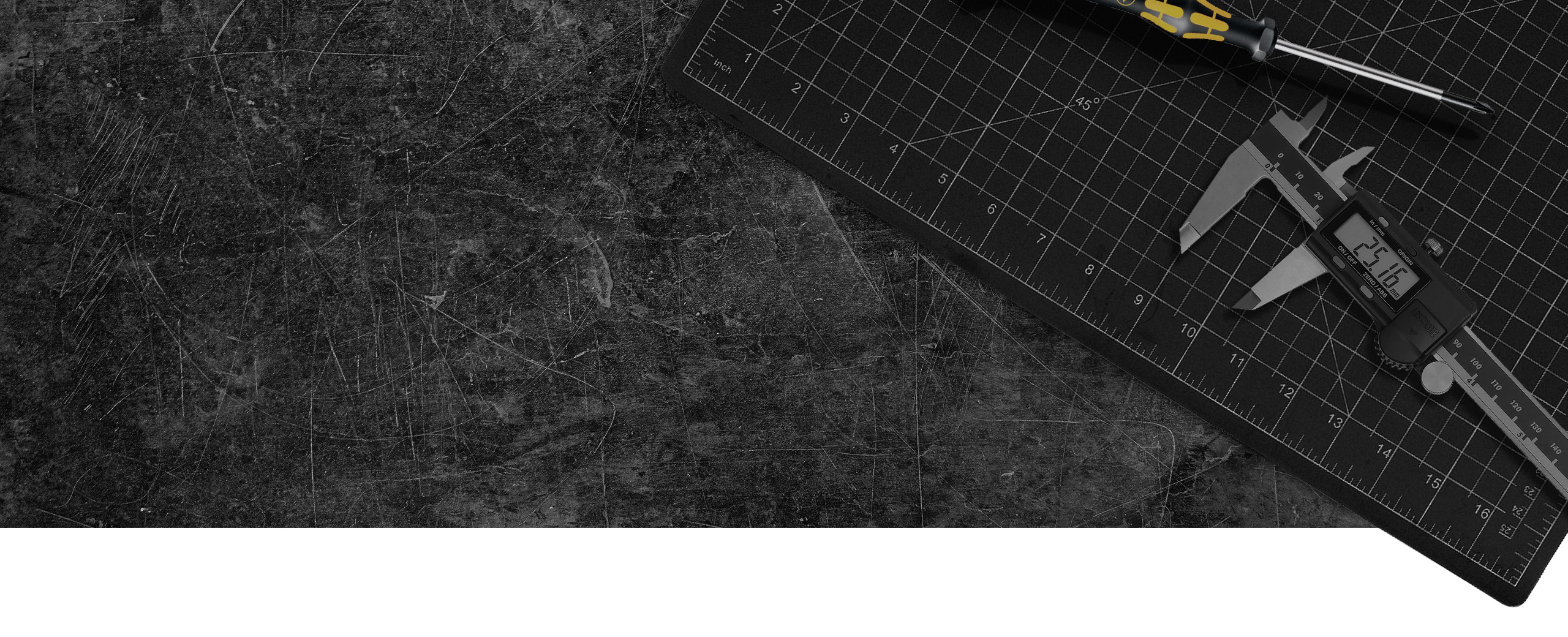

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER SMART CARD READER MAGNETIC STRIPE READER 2D BARCODE READER

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

Compatible models:

BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models:

BioFlex® Smartphones

“We have no idea what’s going on” is a bad headline

As reported by the Washington Post, the evidence for a spike in the homicide rate is mighty thin. Despite the alarming headlines, the changes have not been very dramatic. It is impossible to tell if the recent spike in some cities is a genuine change or a simply a normal variation.

Crime statistics are notoriously variable. A single domestic incident may raise the annual murder rate for a medium-size town from 4 victims to 5 victims. That’s a 25% increase, far larger than the homicide rate spike that we have been discussing.

The lack of definitive proof hasn’t stop people from reaching conclusions based on their preconceived notions or trying to exploit headlines for political gain. No police chief ever went to a town council and said, “I need a big budget increase, because the crime rate has significantly fallen.” No newspaper ever ran a headline with “FBI releases inconclusive and meaningless statistics.”

Of course, the recent homicide increase could be a start of a disturbing trend. However, we won’t know for months, if not years. Before we start manning the barricades, let’s take a deep breath, and evaluate the evidence rationally.

Wouldn’t it be great if someone ran the headline, “Politicians and media figures urge calm intelligent action”? That would definitely be a new trend.

On September 14, Ahmed Mohamed was arrested for having a fake bomb. He never claimed he had a bomb, fake or otherwise. Under stressful interrogation by police, he repeatedly claimed, as he had all along, that the clock was, in fact, a clock. Though the police agreed that the homemade device was indeed a clock, they arrested Ahmed anyway.

Ahmed was handcuffed and suspended from school. His story has a happy ending in that charges were dropped, and many powerful people reached out to him. By invitation, he’ll be touring FaceBook, Google, and the White House.

While many people have focused on the bigotry angle of Ahmed’s story (would he have been arrested if had not been a Moslem?), there is another aspect that is also troubling. To put it bluntly, many of the people involved in his arrest acted stupidly. It should have been quite evident very early on that no crime had been committed, and that this 14-year old was no threat at all. Yet, both the school and law enforcement have stubbornly insisted that their actions were appropriate.

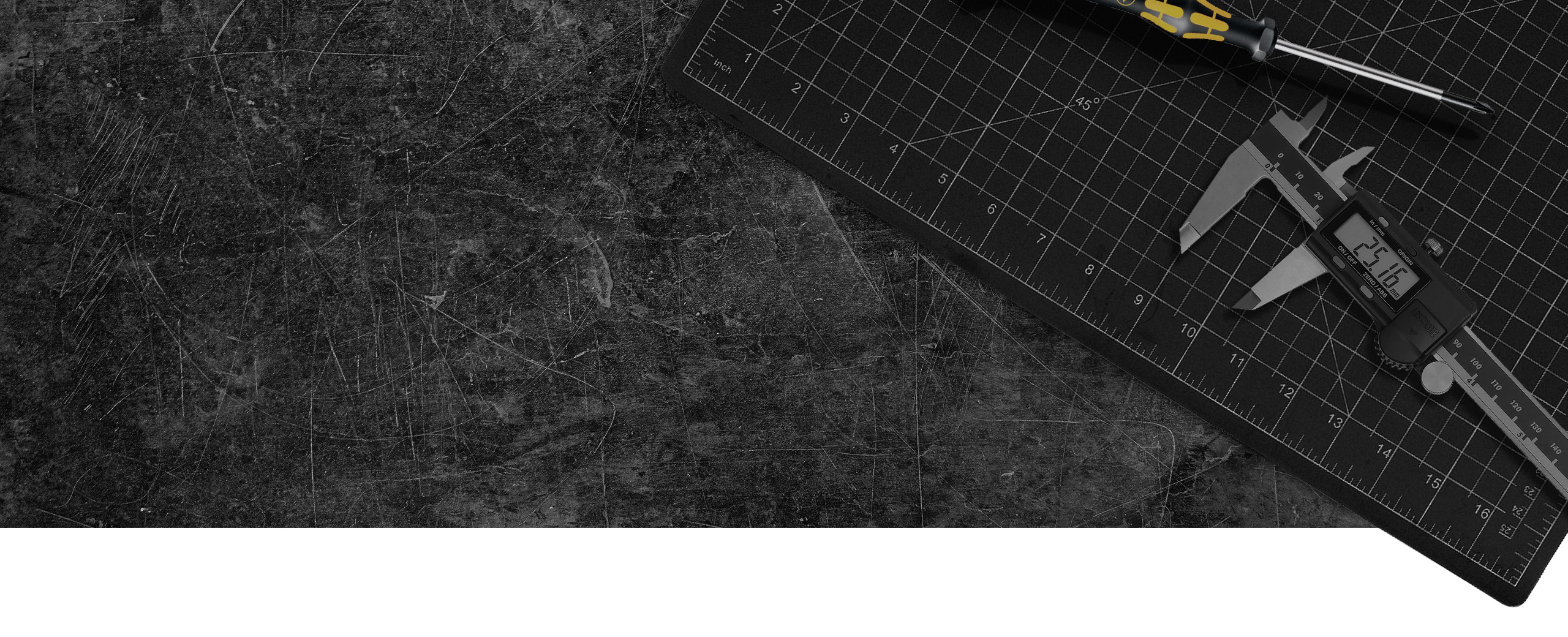

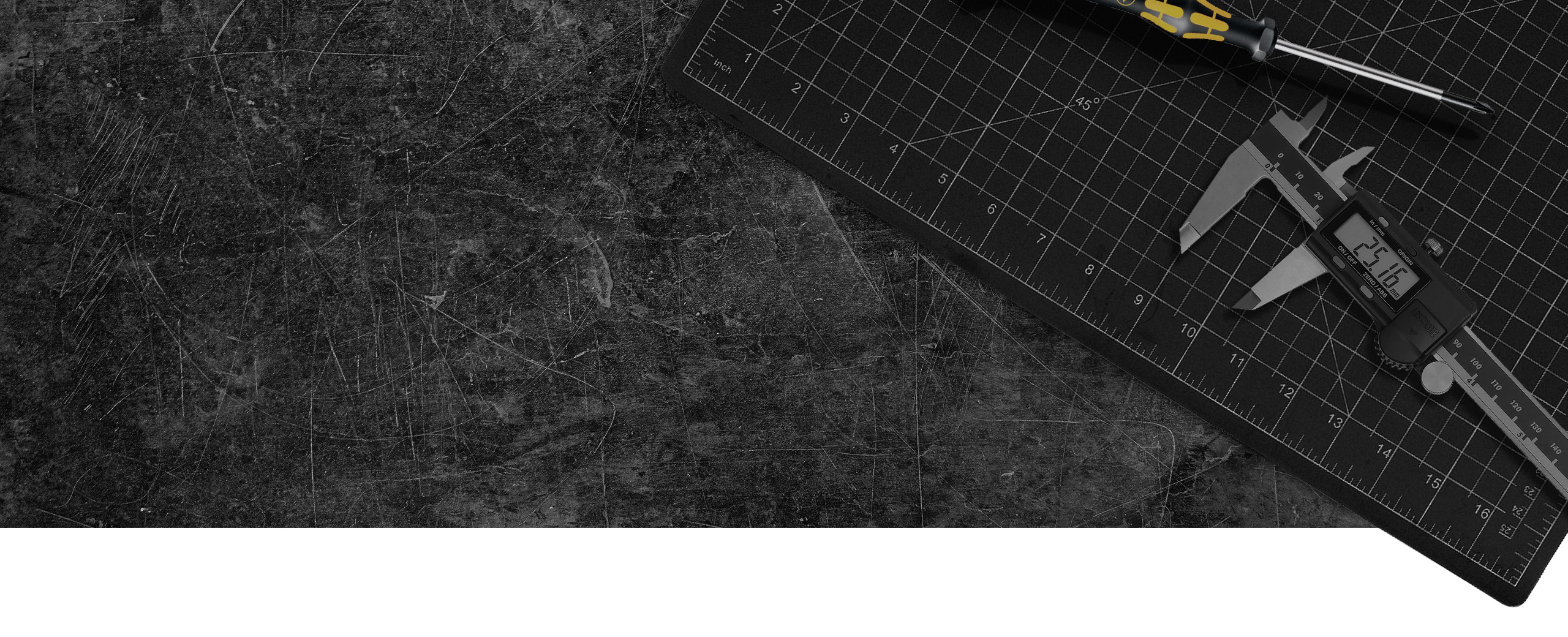

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

SMART CARD READER

MAGNETIC STRIPE READER

2D BARCODE READER

Compatible models: BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models: BioFlex® Smartphones

Nobody expects police, the judiciary, and teachers to be experts about explosives and dangerous devices. However, it seems obvious that when confronted by a technology of which you are suspicious, one should consult a professional to make an informed assessment. It is also obvious that when one makes a blatant mistake, one should admit it and move on.

Shockingly, Ahmed’s story is not unique. A quick internet searched revealed a surprisingly high number of incidents in which innocent people’s lives were disrupted under similar circumstances.

- Sixteen-year old Kiera Wilmot did what kids have done since time immemorial: created a volcano experiment at a science fair. After an uneventful, successful demonstration, she was promptly arrested, suspended from school, and charged with 2 felonies, which were later dropped. She is now a sophomore at Florida Polytechnic University.

- Steve Kurtz, a professor of art, sometimes uses biological materials in his installations. FBI raided his home and charged him with bioterrorism. Despite Commissioner of Public Health for New York State ruling that nothing in his home posed a threat, federal authorities still brought charges. After a grand jury refused to indict him on bioterrorism, he was charged with other felonies. A genetics professor who assisted him with his art projects was also indicted. Four years after the initial charges, a judge ruled that no crime had been committed.

- Lewis Casey, an 18-year-old university student, built a chemistry lab in his home for his studies. Police arrested him for running a meth lab. After it became abundantly clear to even the most clueless observer, that Casey’s lab had nothing to do with meth, he was charged with terrorism and bomb making. More than a year after his arrest he worked out a plea deal, paid a fine, will not have a criminal record, and will be able to return to his studies at university.

- Xi Xiaoxing, the chairman of Temple University’s physics department was arrested for passing secrets to the Chinese. The evidence was a diagram he had sent overseas. The federal authorities claimed it was for a sensitive piece of technology called a pocket heater. Months after he was led away in handcuffs, suspended from his job, stripped of his title of chairman, and had his long-term research disrupted, expert testimony convinced the feds that the suspicious diagram was nothing like the pocket heater. Charges were dropped.

I have other examples. A hydrologist for the National Weather Service was cleared of all spying charges, but still risks losing her job. Even rapper/actor Ice-T was arrested for having a fake bomb, a clock that he had bought at the mall.

Although the spying episodes may seem different than the fake bomb incidents, they share a similar pattern:

- Authorities see a technology that arouses fear.

- Without really understanding what they see, they arrest the suspect.

- They fail to consult experts about what the technology really is.

- Even when the suspect is cleared of the original charges, authorities will refuse to admit they made a mistake and even sometimes bring further unrelated charges.

If you are alarmed by this, you are not alone. More and more people are becoming concerned about the “Freedom to Tinker.” Hackers, makers, and other technophiles are frightened that their creativity will be stifled by an authoritarian, permission-based culture. This is not a simple matter in that it impacts copyright law, counterterrorism, patents, and a host of other issues.

The outreach by technological giants to the Texas teenager was motivated by more than simple outrage against an injustice. Some important innovators in the hi-tech world are frightened that the playfulness – the joy – of experimentation by young folks is under attack. This could be significant detriment to technological development. As someone once remarked to me, “The construction of every bridge began with a child playing with blocks.”

I was raised on stories about the great inventors like the Wright brothers, Thomas Edison, and Alexander Graham Bell. I grew up thinking that inventiveness was a core American virtue. I fear that when our current generation listens to the inspiring story of bicycle repairmen from Ohio inventing the first heavier-than-air flying machine, they will inevitably ask, “When were the Wright brothers arrested for building Weapons of Mass Destruction?”

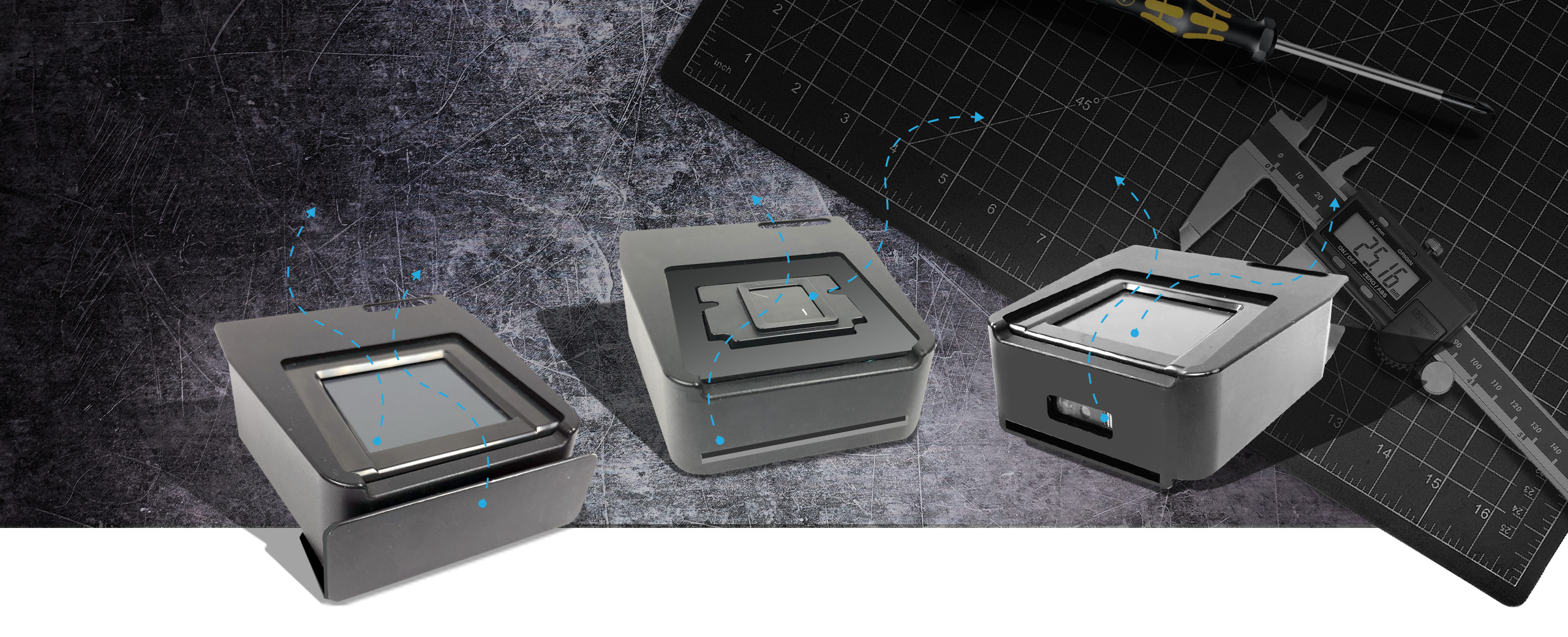

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

SMART CARD READER

MAGNETIC STRIPE READER

2D BARCODE READER

Compatible models: BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models: BioFlex® Smartphones

The topic of illegal immigration usually inspires technical talk at AMREL. Is the handheld biometric XP7-ID a preferred solution for border patrol agents, or do they favor the wider display of the Flexpedient® AT-80B tablet? Which components of the compact 19”/2® Network Servers are appropriate for a mobile communication solution that would service the remote areas of the American Southwest? Can the positive experiences that the military had with our Operator Control Unit (OCU) solutions for unmanned systems be repeated with the recently ramped up border security forces?

However, one afternoon we shelved talks of networks and laptops for a more personal approach. In a typical “water cooler” conversation, we discussed our attitudes toward this hot topic. What I noticed was that even though everyone had been born in this country, our opinions had been shaped by our families’ experiences with immigration. Americans like to think of themselves as independent of history, and that our views are purely rational, but it seems to me in this instance, what you believe reflects who you are and where you come from.

I asked my fellow co-workers to write down how their family histories affected their views on immigration. You may be surprised at who expressed what views.

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

SMART CARD READER

MAGNETIC STRIPE READER

2D BARCODE READER

Compatible models: BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models: BioFlex® Smartphones

William Finn

AMREL Senior Editor & Copywriter

Most of my family tree dates back in this country to the late 1800s. They fled pogroms, 25-year draft sentences, and whatever delightful things Eastern Europeans had reserved for the Jews.

We were legal immigrants, but more significantly America was the first country where we were legal residents. Despite having lived in some European communities for over a thousand years, we never had the privileges and rights afforded our Christian neighbors. United States was the first country to ever recognize us with actual citizenship. As a result, I don’t think anyone was more pro-American that my grandparents and great grandparents.

Our current generations are deeply involved with the law (family dinners often include probation officers, and a judge). We take the rule of law very seriously, but that doesn’t mean we take a hard line on immigration.

Despite generations of American privilege, the ghosts of rampaging Cossacks, bone crushing poverty, and tyrannical bureaucrats still haunt us. Our family history is full of ancestors who had no documented status in the towns where they were born. We understand better than most what a desperate person will do to protect their loved ones. We look at illegal immigrants and see ourselves.

Illegal immigration is unquestionably a problem for some. Economists tell us that for the country as a whole, the financial pluses and minuses of illegal immigration average out. The problem is that no one lives in the “country as a whole.” Whenever a politician talks about illegal immigration, I never hear them offering solutions for the people and communities negatively affected by illegal immigration. Sometimes, I think they care more about hurting illegals than they do about helping our country.

Frankly, I just don’t see illegal immigration as that big of a deal. Maybe if I was a construction worker who lost his job to an illegal immigrant I might feel differently. Maybe if I hadn’t grown up in the Arizona, where I spent afternoons with my father watching bullfights on a local TV station, and my family argued over guacamole recipes, I might view Latino culture as foreign rather than intrinsically American.

I do see other problems in this country:

- In 2007, the world economy lost 8 trillion dollars due to irresponsible deregulation and shenanigans by the financial sector. Like millions of others, I lost my job and my house. No one responsible went to jail. I don’t think any of the main players even lost their job. The country still hasn’t fully recovered.

- The infrastructure of this country is decaying and needs a massive build up, but Congress has done diddlysquat about this problem.

- Our doctors may be great, but our healthcare system is the most expensive in the world. It is a drag on the economy, with every business paying an invisible tax to this terribly inefficient system.

I could go on, but what do all these problems have in common? They have nothing to do with illegal immigration. Remind me again, why are we talking about this?

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

SMART CARD READER

MAGNETIC STRIPE READER

2D BARCODE READER

Compatible models: BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models: BioFlex® Smartphones

Richard Barrios

Web Marketing Specialist

I am proud of my heritage and the roots of my family. As my Dad would say, “I am an American not a Mexican.”

Immigration is a very personal issue for me. My mother’s side of the family came here from South America on visas and worked their way to citizenship. My father was born in the United States from immigrant parents that came to the US in the 1930’s. My wife and her family are also naturalized citizens, but from the Philippines.

I am Hispanic and grew up in a Hispanic home and in a Hispanic neighborhood. I know that many will call me a self hating Hispanic and racist. However, illegal immigration and the activism to legitimize it is a slap in the face to my family. Plain and simple. Both my family and my wife’s do not understand the fight to legalize those who broke the law and want preferential treatment.

My wife’s cousin, who lives in the Philippines, has applied to come to the United States and has to wait 10 years. He is a registered nurse and runs his own business. Meanwhile, illegal immigrants sit in the United States and wait for the next amnesty law to take effect. The illegal works here, establishes himself with references, and has children. The children are citizens and now this illegal alien has additional arguments to stay in the country (Dream Act).

Federal Government is asked to protect the border and won’t do it. Instead they spend millions on amnesty programs and trying to convince Americans that Mexico and Mexicans are not the problem. I have heard many people say that it is impossible to deport or send 11 Million illegal aliens out of the United States. Then how did 11 Million people come to the United States if it’s impossible to move that many people in the first place? How about they leave the same way they came and all others on a case by case basis.

Something that many haven’t taken into account are the resources that are available. From money, to housing, to jobs, legal immigration, roads and natural resources. The child of an illegal is eligible for welfare and thus qualifies the family for all the other benefits. Another way to qualify is using false papers. Stealing Social Security numbers and paper work of legal immigrants is very common. How do you think 11 Million illegal aliens live and work in this country? Without closing the border and creating a legal way in, the money that needs to be allocated to support less fortunate can never be assessed correctly from year to year. This unchecked immigration issue also hinders people that want to come here legitimately. My wife’s cousin for example.

Natural resources, like water, also becomes an issue. In order to support a population one needs to have control over how many people come into the environment. Governor Brown of California said recently, said “If they did so, the state would not only support its current population of 39 million, but probably could accept at least 10 million more residents.” If illegal immigration is left unchecked we will quickly exceed the numbers we can support. At current rates California should reach 50 million residents by 2050, then what?

Growing up, I found an overwhelming majority of Mexican Americans, even US born, consider themselves Mexicans first and Americans second. Stark contrast to the vast majority of Asians, Europeans and Africans who immigrate to this country and are proud to be called Americans.

Today, the distinction of rights afforded to an American citizen and an illegal alien is nearly gone. What is left? There are over 200 sanctuary cities across the country who have explicitly committed themselves to ignore federal law and will not cooperate with ICE. Public policy has given illegal aliens more rights than an American citizen under the law. If I break a state or federal law is there a sanctuary city for me? If I break the law (non violent) and get sent to jail for a number of years, is the state not separating me from my family and taking away the bread winner?

Tens of thousands of American service men have bled and died for the rights and freedoms we have in the United States, not for Mexicans to have rights to the United States.

Albaro Ibarra

Senior Marketing Manager

Both of my parents came to the USA from Mexico legally. My mother went through the process at a young age and secured her Green Card. Her older brother that came here first then helped the other siblings. My father received his Green Card with help from his boss when he was working in the fields of Coachella picking vegetables.

When both were in their 40’s, they finally became US citizens. Both initially had thoughts of returning back to Mexico, but when they had kids they realized that a better life could be had here. The USA is their home. Their roots are now here. They would not return to Mexico, but they call themselves Mexicans.

My brother and I are First Generation Americans. My primary language is English, but I can read and talk in Spanish (not as fluent in writing). My mind thinks in English first and when I am around Spanish dominant speakers my mind thinks in Spanish until I come across a subject or word or phrase that I don’t know. I tell you this, so you can understand how a First Generation American thinks, compared to someone that grew up in Mexico or a 2+ generation American.

The latest census says that the amount of Latinos in the USA that were born outside of the USA is smaller than those born here. This is a recent change; before the ratios were reversed.

This generation will be bilingual or English dominant. They consider themselves Americans but have Latino cultural ties. The concern I have is that those cultural ties are weakened with each generation. It is a conscious effort on the behalf of my wife and I to have our kids speak Spanish and understand their grandparents’ rich culture. They want to learn, but they can’t relate. When I took them to Mexico on a visit, they were seen as America, not Latinos. The more generations that go by I fear those connections to the Latin cultural will be weakened to the point where one of my great grandchildren would not know they are Latino until they do a school project to check their family tree.

I believe a balance is the best thing. If you are born here, you are American but you should not be punished because of your cultural ties. What makes America so great is its diversity. It is that diversity that makes us stronger and more exciting as a people. We are that great melting pot that has food and spices from all over….what a delicious dish. Who want to eat the same thing every day?

I do believe in enforcing immigration laws, but not building a huge wall. I believe we should have a form of identification for everyone who lives in the USA, because I believe it would help identify potential threats to our country, and help improve the situation about undocumented people receiving medical aid or other State or Federal Services. I am not a cruel beast and don’t believe that if you are here illegally you should not receive basic human rights. What I am against is the people that want to take advantage of the system and the lack of tracking or documentation costs us millions.

My parents believe the same way, even though I do have family members that are very well off, but work the system to get FREE State of Federal aid. I don’t think that is a Latino thing, more a moral thing.

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Tablet Modules

SINGLE FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

DUAL FINGERPRINT SCANNER

SMART CARD READER

MAGNETIC STRIPE READER

2D BARCODE READER

Compatible models: BioSense & BIOPTIX Tablets

Build-Your-Own-Module (BYOM)

Smartphone Modules

DUAL FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

SINGLE FAP45 FINGERPRINT MODULE

Compatible models: BioFlex® Smartphones

Conclusion

There you have it. Three different people with three different family histories on immigration, and three different attitudes toward illegal immigration. Even though we disagree, we respect each other’s opinions. I think a large part of that is that we understand how our past and our family histories have shaped our experiences. Hopefully, others will have the same tolerance in this contentious debate.

The opinion expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the positions of AMREL, its partners, or its other employees.

Do you have an opinion? Send it to editor@amrel.com. Be advised we may use the content of your email in a future blog post.

Sometimes the best way to learn about a subject is just to listen to a bunch of well-informed people sit around and casually discuss it. This is the basis of AMREL’s Rugged Radio Podcast, in which we talk about the so-called “militarization of police.”

William M. Arkin, writing in Gawker, has turned this controversy on its head by contending that soldiers are becoming more like police. His article is worth reading in full and you can access it here.

Arkin cites the rise of biometrics enabled intelligence as well as forensics enabled intelligence as evidence of how soldiers are adopting police tactics. For reasons unclear to me, he writes that counter-IED efforts are also police-type activities. He ends his post with the dramatic, if somewhat ominous, “The world has become a crime scene.”

I was curious what AMREL’s local military experts thought about this article. So I sought the opinion of Rob Culver, Director of Program Management for AMREL. A former U.S. Army Special Forces soldier (AKA Green Beret), he has 23 years of experience in the Army.

Rather than describe his reaction, I’ll just let you read it in a slightly edited form:

“This is the most ****** up article I’ve read in a while.

“Arkin is skilled at weaving words to create the semblance of a pattern that does not exist.

“He goes from the assumption that ‘forensics is a police-only tool to the conclusion that the ‘world has become a crime scene.’ Catchy. What the hell does that mean anyway?

“What he describes as forensics can also be termed Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield (IPB). In the conduct of IPB, you evaluate the terrain. Slow go/no go terrain. Swamps, rivers, bridges, mountains, open spaces. You also evaluate population density and characteristics, i.e. who supports U.S. activities versus those who oppose us. Also, you evaluate ever increasingly the more complicated relationships such as Sunnis and Shias and Kurds etc… Frenemies. It gets complicated. But, it has always been part of military training and operations.

“When the Indian scout jumps off his horse and examines the hoof tracks and droppings in the trail, he can tell how long ago the enemy was there, how many, how heavy, the condition of the horses as well as what the horses have been eating. Using his special Indian scout database (all that information stuck in his brain by his elders, training, and experience), he determines where the closest food source is for what the horses have been eating, and…. abracadabra – forensics! It has been a part of warfare since a patrol from one tribe started tracking a raiding party from another tribe.

“As for biometrics, it has always been part of military operations and population and movement control. Special Forces teams in Vietnam used fingerprints identification to ensure they were not double paying local guerrilla forces (Montagnards, etc.).The difference is instead of using our eyeballs to observe and measure, we have high tech gadgets. Still does not make it police work.

“Everything Arkin refers to can be found in the ‘Small Wars Manual: United States Marine Corps 1940.’ Yep. That is pre WW II. The only difference is the technology and terminology.

“For some reason Arkin states: ‘The Navy, always the single manager for explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) technology, which includes technical exploitation of recovered explosives, explosive devices, and other explosive hazards, is more heavily involved in weapons technical intelligence and exploitation than ever before.’

“To which I reply, yes. IEDs are an explosive hazard and in the past decade posed a greater threat to our forces than previously. What is your point William? How is protecting military forces and local populations during operations NOT a military responsibility?

“Arkin also states ‘Because, ironically, if military’s role is merely collecting evidence, then the fundamental post-9/11 talking point that terrorism is not a law enforcement matter needs to be revised.’ This premise is so flawed; I gag and do not know where to begin. If you think, all our military is doing, is collecting evidence these days… I don’t even know what world you inhabit.

“Also, ‘…as if the experiences of the past 14 years governs or should govern how the United States forms, trains and equips its military.’ Why yes it should, William. Along with, and in context with our previous 200 years of warfare. Or, Mr. Arkin, do you suggest we ignore the lessons learned of the past 14 years of conflict? Again, this article is so flawed from the very beginning of its premise; I do not know where to start.

“In this article, Arkin referenced his other article Improvised Explosive Devices Are Reducing Our Freedoms. From that I found this excerpt. ‘But now wherever and whomever the perpetrator, ‘bomb’ has been rebranded as IED and turned into a supposed tool and act of terror.’

“Yes William, IED is a newer and more accurate description of some types of bombs. For those who have driven through an IED ambush, there is no doubt that an IED is a ‘tool and act of terror.’ Nothing ‘supposed about it.

“Arkin, you are wrong.”

For those who don’t know Rob, he is a pretty easy going guy, so his strongly worded response was a bit of a surprise. I found some of Rob’s points convincing, but I think he may be missing the bigger picture. My reply to him:

“I think you may be right on the money on the specifics, but not the overall point. Sure identifying the enemy and collecting intelligence have always been traditional activities in war. While military operations have always involved elements of policing, haven’t policing missions overwhelmed what has been regarded as traditional military actions? Isn’t this a natural consequence of asymmetric warfare?

“Seems to me that at the beginning of the Iraq/Afghanistan mess, I heard more than one brass hat complaining that the military was doing a job it wasn’t trained for. In other words, we know how to take out tank formations and infantry in trenches, but how are we supposed to patrol neighborhoods?

“When I lived in Israel, I heard this argument a lot. The military was worried that their decades-long mission of patrolling the disputed territories was eroding their abilities to fight a traditional war. Israel’s less-than-stellar performance during the Second Lebanon War seemed, to many, to reinforce this fear (Personally, I blame the Lebanon fiasco on staggeringly incompetent civilian leadership).

“You are right that stuff like biometrics and ISR have always been the province of the military. But the missions have changed. Most of the wars fought post-World War II have not been World War II style wars. The only one I can think of was the First Gulf War. That war was a cakewalk, because our military was designed to fight it. Everything else has been a problem, and despite everyone’s efforts, it doesn’t seem like we have figured out a solution.

“Three other points:

- In the wake of Ferguson there’s has been a lot of talk about the militarization of police. I read comments in news articles by veterans stating they would never act as the police in Ferguson do. Trained in counter insurgency, soldiers know better than to point automatic weapons at peaceful demonstrators. Furthermore, the veterans thought the police were wildly over armored and over armed for their mission. Also, soldiers look for ways to deescalate a situation, something some cops obviously haven’t learned. As I have written before, I think the problem is that the police are not militarized enough.

- 9/11 was in some ways the beginning of the ‘War on terror.’ The NYPD declared the ruins of the World Trade Center a ‘crime scene,’ and repeatedly reminded everyone about this. Indeed, the ‘world is a crime scene.’

- The article mentioned the old argument ‘Is the terrorism a criminal or a military problem?’ It’s a military problem when we want to use the military. It’s a criminal problem when we want to ignore the military code of justice (Sorry Red Cross, no prisoners of war here!). It’s a military problem when we want to ignore the constitutional rights of accused criminals. Those special courts in Guantanamo are a travesty and ineffectual as well. US prosecutors have had a better success record in regular courts.

“As I wrote above, I agree with your criticisms about the article, but I think his overall point may be valid.”

Rob wrote back:

“You might be right. You do make your points. Arkin, tho’, has a track record.

“We got fat and lazy. The only war we (The Military) were gearing up and training for, involved the godless communist hordes roaring across the Fulda Gap, where we would stop them, standing toe-to-toe, trading tactical nuke for tactical nuke. Thank God that didn’t happen. But it was easy on the military mind. Might and Right.

“But where do these wars fit in? Barbary Wars, the Banana Wars, Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, Moro Rebellion, Boxer Rebellion, Poncho Villa Expedition, etc.

“I guess you have to start with a definition of traditional military actions, which means ensuring we differentiate between the mission of the infantry and the mission of our nation’s military. I would argue that our nation’s military is a tool with applications far beyond ‘close with and destroy the enemy.’

“The US Military is conducting joint airborne operations with Latvian forces this week. Just a training exercise. But why? To get better at jumping? Or does it have something to do with containing Russia?

“Yeah, it is a lot simpler when the bad guys wear bad-guy uniforms and the good guys wear US uniforms and the civilians live somewhere completely ‘not here.’ But that nostalgia is based on fantasy. It never has been that way. During World War II in Europe, homes were bombed and civilian lives were shattered. Crime was rampant.

“War has never been simple. It has always been messy. And there is always some ***** that thinks we should ‘kill them all and let God sort them out’ or ‘bomb them back to the Stone Age.’ Anything less is ‘not our job.’ But despite TV, movies, and brass-hatted jack assess, that has never been ‘The Mission’.

“Is terrorism a crime or an act of war? I think, in general, what we frequently call domestic terrorism should be treated as a crime. Terrorism can be a tool of criminals such as drug cartels and mafias, as well as military. Terrorism on US Soil conducted by outside elements is war. Terror conducted by US Citizens, overseas, against US asset is war. Was Johnny Walker Lindh a criminal or an enemy combatant? We already know he is a dumbass. I say ‘enemy combatant.’ I don’t think he belongs in a penitentiary; he belongs in a POW camp. Nor do I think he deserved a civilian trial.”

I’ll let Rob get the last word (for now). What do you think? Have the military’s missions become mere policing? Is terrorism a legal or military problem? Send your opinion to editor@amrel.com

The opinions discussed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of AMREL, its employees, clients or partners.

Paranoia in the pines

Paranoia in the pines

A few months ago, I went to a music festival in the deep woods. In a remote location, thousands of people gathered to have a good time.

The only fly in the ointment was the rampant paranoia. Planes and helicopters were constantly circling overhead. Rumors came fast and furious. Several times, a festival participant informed me that the aircraft were scanning the crowds using facial recognition technology to capture images that would be evaluated for outstanding warrants. Some people at the festival had previous brushes with the law. More significantly, many feared that local law enforcement wanted to raise revenue for their jurisdiction; they thought that facial recognition technology would enable law officers to identify and arrest festival goers on spurious charges.

Wherever I went at the festival, I did my best to dispel these fears. Such technology doesn’t exist yet, I told disbelieving music lovers. Even if it did, it would be used by the NSA or CIA to search for high-value targets in Waziristan, not by a small town sheriff looking at someone dancing in a drum circle (a forest ranger told me the aircraft were privately owned by rich people who wanted to scope out the crowd, probably looking for scantily clad women).

The FBI is working hard to justify your paranoia

I thought of these rumors when I read FBI’s announcement about their Next Generation Identification (NGI) System. Among the many touted improvements are:

“Currently, the IAFIS (Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System) can accept photographs (mugshots) with criminal ten-print submissions. The Interstate Photo System (IPS) will allow customers to add photographs to previously submitted arrest data, submit photos with civil submissions, and submit photos in bulk formats. The IPS will also allow for easier retrieval of photos, and include the ability to accept and search for photographs of scars, marks, and tattoos. In addition, this initiative will also explore the capability of facial recognition technology.”

As mentioned above, the FBI already has the national database of IAFIS for fingerprints. They plan to include iris and facial recognition, because:

“The future of identification systems is currently progressing beyond the dependency of a unimodal (e.g., fingerprint) biometric identifier towards multimodal biometrics (i.e., voice, iris, facial, etc.)…Once developed and implemented, the NGI initiatives and multimodal functionality will promote a high level of information sharing, support interoperability, and provide a foundation for using multiple biometrics for positive identification.”

Sounds like the FBI is making the festival goers’ paranoia a reality, not just in terms of implementing new technology, but also in expanding access to these new tools. As Al Jazeera America put it:

“The FBI has invested considerable energy in recent months in marketing a massive new biometric database to local cops, whom the agency will rely on to help feed it billions of fingerprints, palm prints, mug shots, iris scans and images of scars, tattoos and other identifiers.”

To learn what police are thinking of the FBI’s biometric initiative, I sent some news clippings to Retired Assistant Chief William Leist of the California Highway Patrol (currently, AMREL’s Director of Public Safety Programs). He let me know that AMREL is already developing solutions that will work with the FBI’s NGI. He wrote to me:

“Gone are the days when law enforcement officers needed to arrest, transport to a jail facility, and print an individual who’s identity was in question. FBI’s NGI and AMREL’s Biometric Mobile ID solution will allow officers to quickly identify suspects in the field. This technology will not only enhance officer safety and efficiency, but will also enhance public safety by allowing officers to remain in the field on proactive patrol. Moreover, because this technology can accommodate in-field biometric database enrollments, it opens a host of other options such as mobile booking or cite and release of low level offenders. I don’t believe NGI will replace fingerprints as the article suggests, but it will certainly enhance our biometric ID capabilities and lead to more bad-guys behind bars.”

So, an experience law officer like Bill Leist is onboard for this initiative, and is even working with AMREL to develop biometric solutions that are compatible with it. I’m all for catching bad guys, but even with great mobile biometric devices, I see a few bugs in this expansive national system of identification.

Who pays for all this?

The hardware for capturing palm prints, iris and facial patterns will impact local police departments’ limited resources. More than one police veteran has told me that “There is no such thing as ‘cop proof’ equipment.” Expensive gear routinely gets trashed in the line of duty. To save money on maintenance and repair, police departments will have to spend extra for fully ruggedized biometric devices.

What about all the legacy devices?

Are cash-strapped departments going to scrap their old equipment, because they are incompatible with the FBI’s NGI? Some kind of FAP45 – compatible “biometric add-on” might help with the problem of heterogeneous hardware.

What about the data?

An even greater financial drain will be the “back end.” Managing and processing the torrent of police-generated images will be more costly than the hardware. Unfortunately, most vendors for these solutions target a few large police departments, so their offerings are overpowered and too expensive for the typical small-to-medium sized agency. A month-to-month Software as a Solution (SaaS) might help departments with tight budgets.

What about the training?

With wearable cameras, push-to-talk radios, portable computers and many other gadgets, an average patrolman is getting overwhelmed with technology. He is also overwhelmed with training for all these wonderful devices. Police are certified yearly on their weapons, but as far as I know, only Virginia regularly tests officers on their radio and communication skills. By seeking high-tech solutions, are we subjecting officers to cognitive overload?

What about FirstNet?

Is the FBI’s NGI compatible with FirstNet, the national program for an interoperable network to transmit Public Safety data? In spite of the publicity Firstnet has generated, some departments are barely aware of its existence. What happens if they buy biometric equipment that is not FirstNet compatible?

Despite my skepticism, it seems likely that the FBI’s vision of an integrated national, multimodal biometric database will be a reality. Perhaps, the next time I am surrounded by festival goers afraid of the eye-the-sky, I won’t so casually dismiss their fears. I will simply assure them that it is unlikely the local police can afford to process the thousands of images generated by such a canvassing operation.

American Reliance, Inc.

789 N Fair Oaks Ave,

Pasadena, CA 91103

Office Hours

Monday-Friday:

8:00 am – 5:00 pm PST

Saturday: Closed

Sunday: Closed

Main: +1 (626) 482-1862

Fax: +1 (626) 226-5716

Email: AskUs@amrel.com

Blog Posts

Mobile Biometric Solutions

Mobile Biometric Smartphones & Tablets

BioFlex S® Commercial Smartphones

BioSense AT80B | 8″ Android Biometric Tablet

BioSense PA5 | 10.1″ (Gen 2) Android Biometric Tablet

BioSense PA5 | 10.1″ Android Biometric Tablet

BIOPTIX PM3B | 7″ Windows Biometric Tablet

BIOPTIX PM5B | 10.1″ Windows Biometric Atom Tablet