It’s a familiar scenario. After an encounter with a policeman, someone lies dead or is severely beaten. Citizens complain about police violence, while the police claim they were acting in self-defense.

It’s a familiar scenario. After an encounter with a policeman, someone lies dead or is severely beaten. Citizens complain about police violence, while the police claim they were acting in self-defense.

It almost doesn’t matter who is telling the truth; suspicions build between law enforcement and the community that they are sworn to protect. The public becomes less cooperative, so Investigations are stalled. The police become more fearful, which leads to more force being used, which generates more distrust, and so on.

Wearable cameras are being touted as a way to break this cycle. To improve their relationship with the community, police in the troubled town of Ferguson, Missouri are getting wearable cameras. It is thought that by providing objective evidence, cameras will ease tensions between the public and law enforcement.

It is a thought that a thousand other police departments are having. Police departments adopting or experimenting with wearable cameras include those in Pittsburgh, Salt Lake City, Hartford, Fort Worth (Texas), Chesapeake (VA), Modesto (CA), San Francisco, Eugene (Oregon), New York City, Owasso (OK), and Rialto(CA).

Rialto, a medium-size city, is the one that you will be hearing about. A well-publicized study concluded wearable cameras reduced use-of force incidents by 50% and citizen complaints by over 80%. Other cities have reported similar results.

“In addition to documenting encounters with the public, wearable cameras can help with the tricky task of identification,” explains Richard Lane, Vice-President of AMREL’s Strategic Business Development. “If the video stream is analyzed by facial recognition software, the officer could, in theory, be informed in real time, if a civilian has warrants or has a dangerous history. This could give officers an extra level of security, which would reduce the tensions between the public and the police.”

Typically, compact cameras are fixed to an officer’s collar, chest, sunglasses, or even a Taser. Battery packs are designed to last for a full shift. Images are uploaded automatically to a central server.

In order to minimize police “editing” the video stream to be unduly favorable, citizen-rights advocates argue that officer should be unable to turn on or off the camera. In this scenario, the camera is always turned on, running 30 second loops, i.e. the continuous video stream is erased every 30 seconds. More extended and permanent recordings are triggered by specific events, such as traffic stops, or activation of a Taser. It is not clear how many departments have adopted these policies.

Police are suspicious

Police, like everyone else are concerned about their privacy. Remember, some are advocating that cameras record all the time, even when the officers are in the bathroom.

The lack of privacy in the modern era has been one of selling points to recalcitrant officers. “You are being video recorded anyway by close-circuit TV or smartphones” argue their superiors. “You might as well have a record that shows your side.”

Patrolmen are also frightened that the video could be used against them by their superiors. What if the higher ranks decide to go after a whistleblower or a union organizer? It would be a relatively simple matter to review hours of video feed in order to find something incriminating. For this and other reasons, privacy activists advocate that all video not related to an investigation should be automatically erased after a week or so.

In New York City, a Federal judge, reacting to the abuses caused by the controversial stop-and-frisk program, ordered the city to investigate the use of wearable cameras. The president of one of the police unions, Patrick Lynch, complained:

“Our members are already weighed down with equipment like escape hoods, mace, flashlights, memo books, asps [i.e., batons], radio, handcuffs and the like. Additional equipment becomes an encumbrance and a safety issue for those carrying it. Given that the root cause of this stop-and-frisk problem is a significant shortage of police officers in local precincts, it seems to us that the monies spent on a bodycam pilot program would be better spent on hiring more police officers and providing them with extensive field training with an experienced officer.”

Nevertheless, it seems that familiarity breeds acceptance. Typical is the experience of the police in Scottsdale, Arizona. At first, the cameras (which are voluntary) were met with suspicions by the officers. Then they saw how the cameras backed up an officer’s version of events, when he faced a spurious complaint. Like officers in other communities, they are beginning to see cameras as their friends.

Cost

The union president quoted above is not the only person concerned about cost. Cameras range usually range from $300 to $400, but can be higher. Competition between two leading providers, Vievu and Taser International, has driven the cost of the cameras down. Furthermore, it is expected that the price-sensitive mobile device industry will produce even cheaper off-the-shelf models.

However, cameras are only one part of the cost. Consider:

- San Francisco will spend $250,000 to put cameras on 50 officers.

- Owasso (OK) Police spent about $31,500 for 35 cameras and approximately $13,500 for data storage.

- NYPD will spend $60,000 to initiate a program with 60 cameras.

- Eugene, Oregon has spent $22,000 on 18 cameras.

- Scottsdale is reported to have spent $995 per camera, plus software.

The mathematically inclined reader will notice that the costs are exceeding the typical prices of cameras. That’s because software and storage expenses are considerable.

Storage costs on the cloud are declining, but will remain a significant expense for years to come. Police are finding, like their counterparts in the military, that managing huge amount of video can be extremely resource intensive.

“One reason that software and information storage are expensive is that vendors typically target the very few really large police departments,” reports Mr. Lane. “More needs to be done in providing scalable solutions to small to middle-size law enforcement entities, perhaps using month-to-month leasing models.”

There is an argument that cameras will pay for themselves. Eugene, Oregon reports that videos often eliminate the need for investigations. Even when the number of complaints went up, the cost of expensive investigations went down. “It’s hard to argue with video,” said Sgt. Larry Crompton.

Privacy

Of course, the big issue is privacy. As pointed out above, police have a right to privacy. Furthermore, they are almost unique in the level of intimacy they encounter with the public. They enter people’s homes, and have physical contact with them.

Privacy activists, such as the ACLU, advocate continuous recording and the “30 second” rule as described above. They also think video images should be routinely be erased after a week or two, in order to protect both the police and the public. Hopefully, this will prevent embarrassing videos of otherwise innocent people from appearing on the internet.

Whether you like the ACLU or not, their recommendations will be a factor in how cameras are used. Click here to see the ACLU proposals.

Access to the videos will be a critical issue. Consider the final paragraph in this article. After quoting all sorts of feel-good statements from the police about the cameras, the newspaper reports:

“Eugene police denied a records request from The Register-Guard for video and complaints against police cited in its reporting. The department cited state public records law that allows an agency to keep secret those records that relate to a personnel investigation into an officer, if no discipline has resulted.”

You see the problem? It is precisely when the police department rules that an officer is innocent that the video should be accessible to the public. That way objective evidence can validate the department’s decision to clear the officer.

Clearly, policies will have an important effect whether cameras live up to their potential of easing civilian/police tensions.

Seeing is not believing

You may have seen this picture before. It is one of the most famous photographs of the 20th century.

It looks like a man dressed as a civilian being summarily executed by a South Vietnamese official. This picture and the video of the same incident became iconic for the anti-war movement. The shooter, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan (South Vietnamese police), was plagued by this photograph for the rest of his life.

The man being shot was Captain Nguyen Van Lem, a leader of a Viet Cong assassination team. He had been caught “red-handed” at a mass grave of 34 bound bodies, which included 7 Vietnamese police officers and their families.

In other words, what the video and picture recorded was a policeman exercising understandable (if not justifiable) revenge against a war criminal who had just murdered fellow officers and their families. What people saw was a wanton act of barbarous brutality.

I found only one source for this story. What is inconvertible is that the photographer, Eddie Adams, deeply regretted the photograph (for which he won a Pulitzer Prize), formally apologized to the shooter, and called him a “hero.” Adams wrote:

“Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world. People believe them; but photographs do lie, even without manipulation. They are only half-truths.”

What we can learn from this example is that cameras are not a panacea for easing tensions between the police and the public. Officers see things differently than civilians. Cameras may provide objective evidence. However, according to at least one celebrated photographer, they will best only provide half of the truth.

OK, maybe not

OK, maybe not

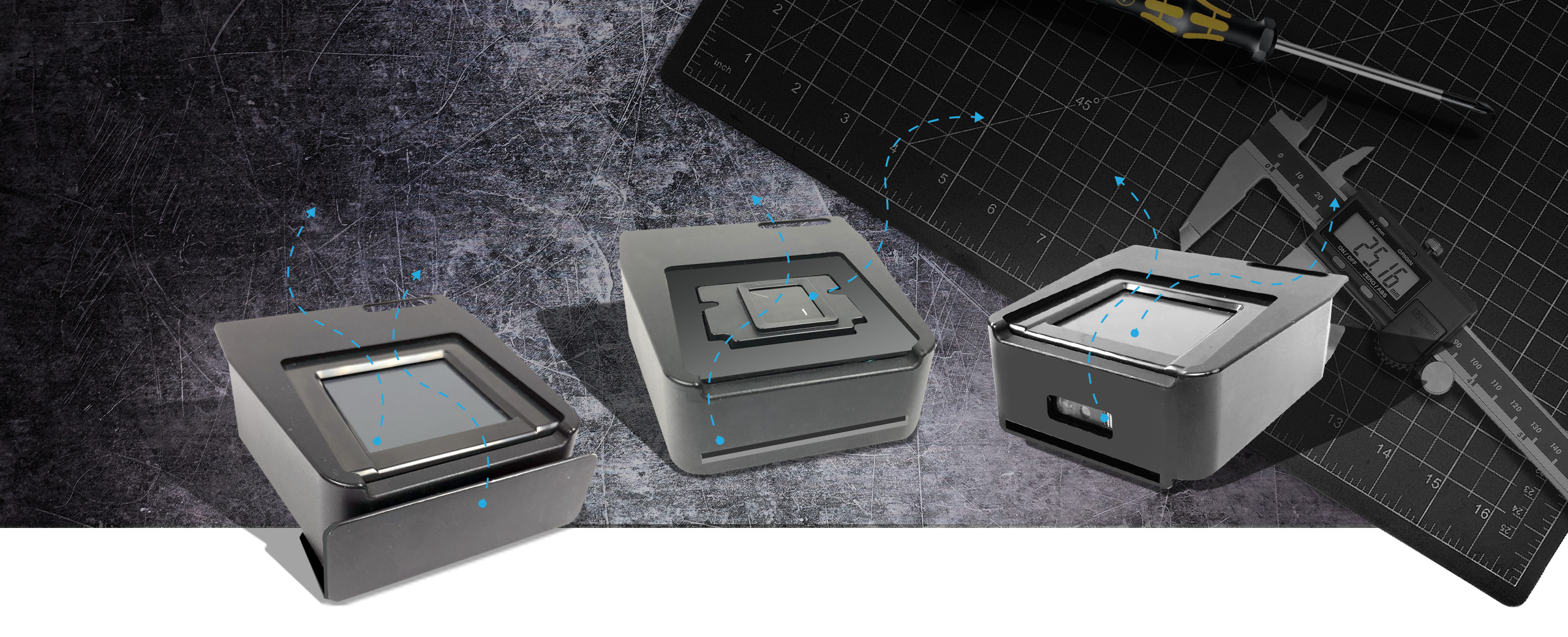

importance of “specs.” Go to any biometric solution provider’ workplace, and you will see highly trained professionals closely examining the latest RFP, eagerly analyzing the specifications, as well as the Scope of Work.

importance of “specs.” Go to any biometric solution provider’ workplace, and you will see highly trained professionals closely examining the latest RFP, eagerly analyzing the specifications, as well as the Scope of Work.