What the heck is an Unmanned Ground Engineering Vehicle?

Recently, Tom Green, founder and editor-in-chief of Robotics Business Review put on a webinar about an Unmanned Ground Engineering Vehicle (UGEV). Before I explain what a UGEV is, a little background.

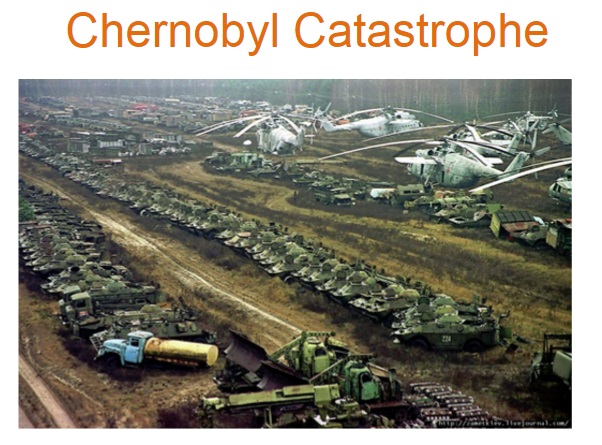

In the webinar, Tom Green noted that we are soon approaching the fifth anniversary of the Fukushima accident and the thirtieth of the Chernobyl disaster. He said that 60,000 Russian (and Ukrainian) workers were exposed to radiation at Chernobyl and that 6,000 have since died (BTW, the exact number of casualties form this accident is fervently debated). Many were critically exposed when they operated vehicles to dump thousands of tons of concrete on the nuclear plant itself. Vehicles are pictured below:

To this day, Green noted, these vehicles are still too irradiated to use. Obviously, many casualties could be avoided if the proper unmanned systems were available. He wondered if anyone had developed an appropriate system. (The lack of nuclear disaster robots was discussed in this blog in: Where are the Japanese robots ).

Unmanned systems operating in nuclear disasters have all sorts of problems. Radiation affects their CCD (electronic light sensor) and other electronics. Clearing away the concrete and rubble can be a formidable task. Green went in search for what he called a “tough boy.”

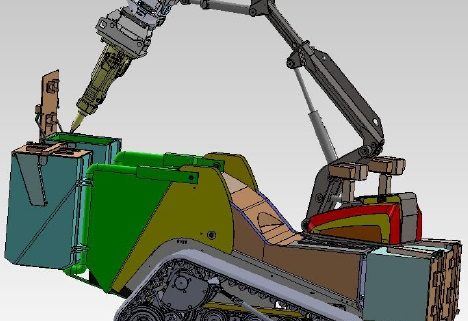

He found one in Tel Aviv. Agritechnique Engineering had developed what is described as an Unmanned Ground Engineering Vehicle (UGEV). Specifically created to operate in nuclear disasters, this UGEV can move as fast as 20KM per hour, has one of the strongest undercarriages on the market, can breach doors, beak down walls, and has a boom that lifts two tons. Built by Avner Opperman (CEO of Agritechnique) who has 40 years of earth-moving experience, Green enthusiastically proclaimed that he had found his “tough boy.”

By far the coolest thing about the UGEV is its versatility. The boom can be fitted with up to 80 different tools, including hydraulic hammers, cutting discs, clamps, and buckets. Carried in attached storage compartments, tools have their own IP. The boom can autonomously switch tools out in the field, matching them to their appropriate tasks. A fully automatic quick coupler hydraulic assembly utilizes the tools with 2 x 55° tilt and endless 360° range of motion.

Opperman designed the flexible tool system with the idea that the UGEV could perform multiple tasks, and be capable of adapting to a wide a variety of needs as they occurred in the field. He wanted an unmanned system that could replace the many different kinds that are used now in disasters.

View video below.

You can read also about it in Robotics Business Review.

My first reaction to the UGEV was favorable. It reminded me of the Flexbay and Flexpedient concepts that AMREL had successfully incorporated into our mobile rugged platforms. We created Operator Control Units with Flexbays that enabled personnel to switch applications in the field. The military loved how it increased operational range and simplified logistics. They deployed thousands in theater. Similarly, our Flexpedient® AT80 tablets can be modified to a wide variety of applications, enabling quick customization. New product developers have seized upon it as a way of getting their solutions to market faster and more economically.

However, it’s one thing to create mobile rugged computer platforms that are interoperable and flexible. It is another to build a vehicle that is an “all in one” unit, i.e. one that replaces a heterogeneous collection of unmanned systems as Opperman advocates.

While UGEV undoubtedly looks capable of clearing away debris and pouring cement (which is what Green was looking for), can it really replace the mixed lot of unmanned systems that are currently used? Is it even a good idea? For one thing, the UGEV is big. It’s 13 feet long and almost 6 feet wide. It’s difficult to imagine it fitting into the narrower spaces in the interior areas of some nuclear plants.

I am not an expert in disaster robotics, but Dr. Robin Murphy of Center for Robot-Assisted Search and Rescue (CRASAR) is. She has written that for disasters: “ground robots are generally not useful” (CRASAR). She has also said that “…there is not a single robot that will work for all missions” (CRASAR).

The biggest problem with the UGEV – and all disaster robotics – is that no one wants to pay for them. Writing for Slate William Slaeton noted, “Power companies want cheap robots that can replace workers and are always useful. They don’t want robots expensively equipped to handle unlikely nightmare scenarios.” They prefer the time-tested technique of pretending nothing bad will ever happen.

What do you think? Is the UGEV the revolution that Green and Opperman think it is, or is it a technological dead-end? Send us your opinions to editor@amrel.com (please note that your messages may be used in future blog posts).